WASHINGTON (CNS) — The setting was the same and some of the issues of the 1963 March on Washington remain, but in many respects, the 50th anniversary observance at the Lincoln Memorial Aug. 28 showed the progress of the nation in the intervening years.

For instance, the speaker who concluded the program of politicians, celebrities, preachers and performers this time also was African-American, President Barack Obama, the first of his heritage to be elected U.S. president.

His address, among the longest of the more than 50 speakers who took the stage, recalled that on that day in 1963 the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., “offered a salvation path for oppressed and oppressors alike. His words belong to the ages, possessing a power and prophecy unmatched in our time.

But, Obama added, the day also belonged to “ordinary people whose names never appeared in the history books, never got on TV. Many had gone to segregated schools and sat at segregated lunch counters. They lived in towns where they couldn’t vote and cities where their votes didn’t matter. They were couples in love who couldn’t marry, soldiers who fought for freedom abroad that they found denied to them at home. They had seen loved ones beaten, and children fire-hosed, and they had every reason to lash out in anger, or resign themselves to a bitter fate.”

Yet they chose another path, Obama continued. “In the face of hatred, they prayed for their tormentors. In the face of violence, they stood up and sat in, with the moral force of nonviolence. Willingly, they went to jail to protest unjust laws, their cells swelling with the sound of freedom songs. A lifetime of indignities had taught them that no man can take away the dignity and grace that God grants us. They had learned through hard experience what Frederick Douglass once taught — that freedom is not given, it must be won, through struggle and discipline, persistence and faith,” the president said.

Other powerful speakers near the end of the hours-long event were again named King, the daughter, son and sister of the Rev. King who mesmerized the 1963 audience and the world with his “I Have a Dream” speech. This time, it was the Rev. Bernice King, CEO of the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change, who echoed her father’s sermon-like call to continue the battle for freedom for all.

Quoting her mother, Rev. King said, “the struggle for freedom is a never-ending process. Freedom is never really won, you win it and earn it in every generation.”

She observed that 50 years earlier, President John F. Kennedy did not attend the rally at the Lincoln Memorial, but this day there were three, with former presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton each taking the stage in the final hour.

Rev. King referred to her father, who died when she was 5, poetically, as a prophet, who had a vision and made it clear, describing the yearnings of people around the world including “the right to have a voice, without disenfranchisement, the right to peacefully coexist.”

She said the anniversary event was an opportunity to rejuvenate the battle against ongoing crippling “practices and policies steeped in racial pride, hatred and hostility, which have some of us standing our ground rather than finding common ground.”

Her brother, Martin Luther King III, explained that he brought his 5-year-old daughter to the event “so she can appreciate this history.”

“I’m reminded that dad challenged us to be a better nation for all God’s children,” King said. “He taught us the power of love, agape love,” the Greek word for brotherly love.

His father, King said, taught that race, color and other differences do not matter “because God loves us all,” and that “sometimes we must take positions that are neither safe nor popular nor politic, but we must take those positions because our conscience tells us they are right.”

“Nobody ever told us our roads would be easy,” King said, “But our God did not bring us this far to leave us.”

As they had 50 years before, thousands of people lined the reflecting pool between the memorial and the Washington Monument. A mixture of races, ages and cultures was apparent, as it was in the photos and films of 1963. An intermittent drizzle kept the crowd huddled under umbrellas much of the day, but it did not appear to deter people from joining the thick clogs at the security checkpoints for access to the grounds of the reflecting pool and Lincoln Memorial.

Unlike the 1963 event, there was no high-profile presence of Catholic clergy on the stage. Then-Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle of Washington, a civil rights promoter in his own right, led off the formal program with a prayer for the nation and its people: “Let us understand that simple justice demands that the rights of all be honored by every man.”

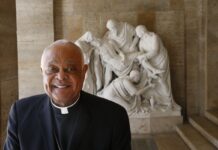

Current Washington archbishop, Cardinal Donald W. Wuerl, participated in a morning interfaith prayer service related to the anniversary, but the clergy on the program at the Lincoln Memorial were all Protestants, including the Rev. Al Sharpton, performer Rev. Wintley Phipps, the Rev. Roslyn Brock, who chairs the NAACP, and civil rights leader the Rev. Joseph Lowery.

— By Patricia Zapor Catholic News Service