GREENWOOD, Miss. (CNS) — A pane of cracked blue glass above the front doors of St. Francis of Assisi Church in Greenwood helps ensure that nobody forgets how their parish, its founding pastor and the religious who staffed it stood up for them during a polarizing, often brutal time.

As this summer marks the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, parishioners at St. Francis have a vivid reminder of the related events in their town. They can look up and see where a bullet went through the window, one of many acts of violence and serious threats to a faith community that was active in promoting civil rights, both behind the scenes and in the streets.

For people who lived in Greenwood at that time, however, the broken window pane doesn’t seem necessary to remind them what their town has been through. In interviews with Catholic News Service in early June, parishioners at St. Francis and the town’s other Catholic church, Immaculate Heart of Mary, spoke vividly of incidents from those years.

They lived with the blatantly racist way of life epitomized by the White Citizens’ Council, a Greenwood-founded segregationist group that actively championed the Jim Crow system. Greenwood, now with a population of just 15,000 and then around 20,000, found itself divided even more in the mid-1960s by a months-long merchant boycott in protest of how blacks were treated. A few years earlier and 10 miles up the road, Emmett Till, the black Chicago 14-year-old who was visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi, was found — tortured and killed — reportedly for flirting with a white young woman.

Greenwood’s residents lived through the two criminal trials of local white supremacist Byron De La Beckwith for murdering civil rights activist Medgar Evers in 1963. (Though those 1960s trials failed to reach verdicts, he was convicted in 1994.)

And Greenwood witnessed further upheaval when organizers from outside Mississippi zeroed in on their town to promote voter education and voter registration, leading to a fire being set at the offices of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the gunshot wounding of a community organizer, even drawing such high profile activists as singers Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger to town.

Through all this, what was then known as St. Francis Mission, its elementary school and church-sponsored community center in the heart of a poor, black neighborhood, were essential pieces of efforts by the Catholic Church in Mississippi to provide a wide range of services to Mississippi’s poorest residents, regardless of religious affiliation. In Greenwood, the Franciscans strove to provide African-Americans with a welcoming place to worship and a school where they could get a decent education in the deeply segregated society.

Mississippi’s Catholic population has never been large — it’s currently about 9 percent — and the percentage of black Catholics is an even smaller fragment. When St. Francis Mission was founded in 1950, there were just two black Catholics in Greenwood, according to an article on the role of Catholics in the town by Siena College professor Paul T. Murray in the Journal of Mississippi History.

Franciscan Father Nathaniel Machesky, a Detroit native who joined the friars out of a desire to do missionary work, was initially assigned in Greenwood at Immaculate Heart of Mary. But as Murray put it, “ministering to a respectable all-white congregation was not Father Nathaniel’s idea of true missionary work.” When the friars received permission to open a mission for African Americans, he found a 12-acre parcel of land on the outskirts of town and transformed the “juke joint” on the property into a chapel.

Fr. Machesky saw offering a good education as the key to evangelization and quickly opened a school at the mission.

Talking over coffee in the rectory in early June, several African-American women who’d grown up at St. Francis, and who became Catholic because their parents put them in school there, told CNS about how far their community has come when it comes to racial divisions.

They told long-ago stories: of being warned to leave a CYO gathering at Immaculate Heart before something bad happened; and of being told during a prayer service there, “This church is ours. You have your own.”

But another woman had a story from just last year: of watching a white man in line at the grocery store demand — and get — a white cashier to ring up his order instead of the black cashier who was already in the position. More than one of the women voiced a fear that “Jim Crow is coming back,” because of the increase in apparently race-based conflicts around the country.

They agreed that the role of St. Francis of Assisi Parish was important to their own success in life, and in helping improve the chances for Greenwood’s poor black families, as well as helping turn the tide against the era’s racist ways.

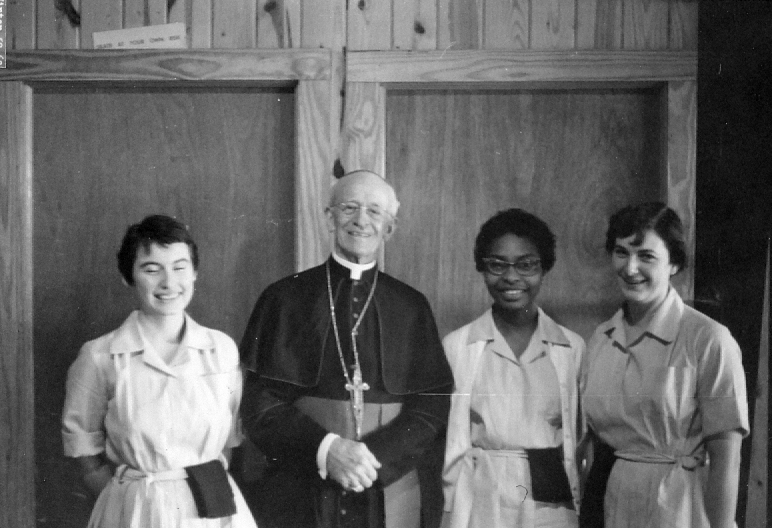

Another piece of the Catholic Church’s role in Greenwood began with Kate Foote Jordan, who founded a secular institute of religious women they called Pax Christi. By the mid-1960s, the group of about 20 women, including two African-Americans, operated the St. Francis Information Center to offer instruction in Catholicism and recreational activities for children, according to Murray.

It eventually hosted a clinic, a grocery store, scout troops, music lessons, a skating rink, tutoring and adult education, and published a weekly newspaper for African-Americans.

Fr. Machesky also created a credit union and several small businesses for the community. He was active in the interracial ministerial association and successfully worked with both blacks and whites in building the parish of St. Francis.

His involvement in the boycott of Greenwood merchants that followed the 1968 murder of Dr. Martin Luther King changed that somewhat.

As one of the priest’s friends and a lifelong Immaculate Heart parishioner, Alex Malouf, tells it, Fr. Machesky had carefully straddled the cultural chasm between his black parishioners and the dominant white business community, where he had friends and supporters.

But the support the parish had enjoyed from some of the white-owned businesses was strained when Fr. Machesky, the sisters who staffed the school and others affiliated with the church joined the boycott of their stores.

One of the African-American women at St. Francis and a white parishioner at Immaculate Heart each told about the nuns getting new tennis shoes courtesy of a Greenwood merchant one week and wearing them in a protest march against the merchants a few days later. Decades later, the story still gets a little different spin when told by a woman who supported the protests and the son of a ’60s merchant.

A bitter legal battle over how protests were conducted and the months-long “unbelievably effective” boycott were finally settled, Malouf said, when he worked with the merchants and Fr. Machesky worked with the African-American community through the ministerial association to negotiate a settlement.

“You could get killed over that,” Malouf said, adding that in those days in Greenwood, such conversations across color lines just didn’t take place. “I was threatened. The Klan threw stuff at my house.”

Fr. Machesky had been threatened quite seriously — a man who said he’d been hired by the Ku Klux Klan to kill the priest came to the rectory one day. The two talked at length and eventually the hired killer said he decided the priest was too good a man to kill and gave back the money. For a time the priest’s brother, a fellow friar, served as a sort of bodyguard, various Greenwood residents said.

As for the boycott, Malouf said the negotiations he and Fr. Machesky helped arrange bore fruit, surprisingly quickly.

The merchants agreed to hire a few African-American employees and to work on getting the city to hire blacks for the police and fire departments. And they agreed to start referring to African-Americans with courtesy titles — Mr. and Mrs., as they did white customers — instead of by their first names.

In return, the boycott ended and Greenwood’s majority black population began patronizing their local businesses again.