VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The COVID-19 pandemic came at the worst time for scholars and historians who had been waiting for the March 2 opening of the Vatican archives’ material that spans the wartime pontificate of Pope Pius XII.

As part of efforts to contain the spread of the coronavirus, the Vatican’s Apostolic Archives — made up of more than 600 archival collections — are closed until further notice.

However, one unique collection of wartime documents had been accessed and studied before the nationwide lockdown: the archives of the Pontifical Gendarmes. The findings, including some never-before-published discoveries, were made available in a recently published book in Italian, “Il Vaticano nella Tormenta” (“The Vatican in the Storm”) by Cesare Catananti.

Known today as the Gendarmerie Corps, the centuries-old police force is charged with protecting the pope, defending the territory of Vatican City State and maintaining law and order within its walls, which was not a tall task for a tiny territory until the storm clouds of World War II rolled in.

‘Il Vaticano nella Tormenta’ (‘The Vatican in the Storm’)

Author: Cesare Catananti

Language: Italian

Publisher: Sao Paulo Edizioni

Publishing Date: Jan. 1, 2020

Length: 351 pp.

The job of the Vatican gendarmes suddenly became harder and riskier when Vatican City — a sovereign and neutral nation — found itself isolated and in potential danger first when fascist Italy joined the war with the Axis powers in 1940, then when Nazi soldiers occupied Rome in 1943 and finally when Rome was liberated, but also occupied, by the Allies in 1944.

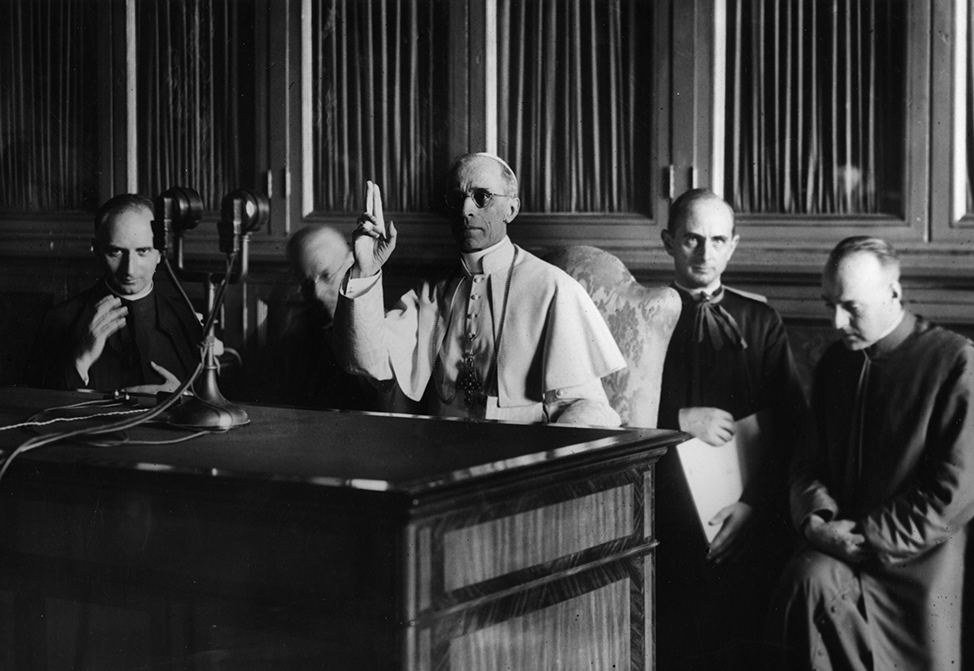

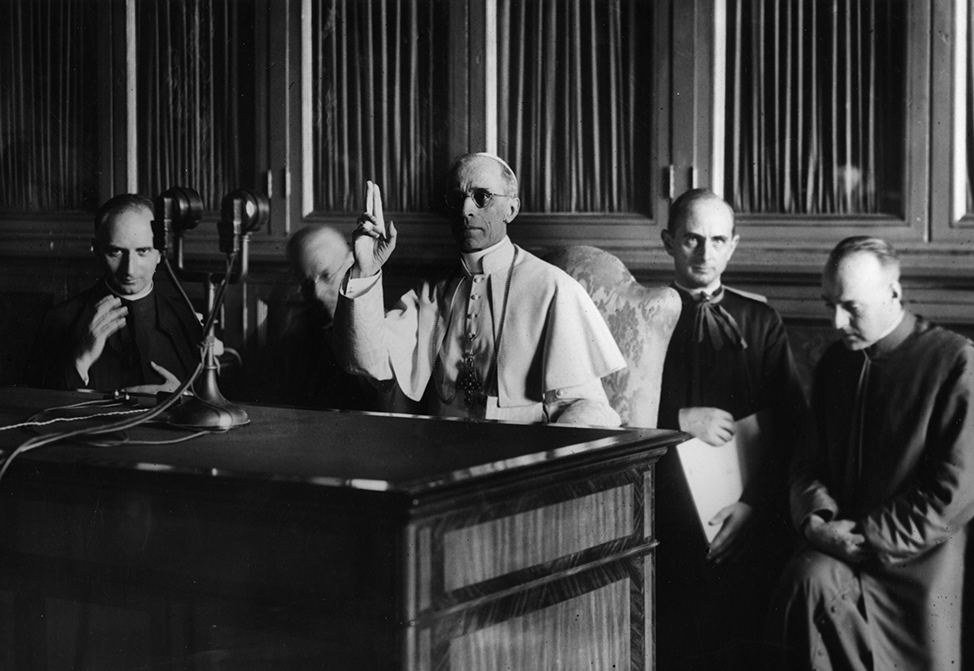

During that period, the gendarmes had to: confront spies within its own ranks; keep an eye on diplomats from Allied countries who moved their posts to safety inside Vatican City, but were also suspected of espionage; contain damage from bombs dropping on Vatican territory; house and feed defecting soldiers seeking asylum; figure out how to deal with the unauthorized comings-and-goings of escaped prisoners of war whom an Irish monsignor was helping in a clandestine Church-run network; and most challenging of all — have a plan ready to defend the life and safety of Pope Pius XII from Adolf Hitler’s threat to kidnap him.

Catananti provides plenty of details of these events from 1940 to 1944 in his 360-page book.

Based on internal memos, written directives the gendarmes’ received from Vatican officials, police reports and other documents found in the archives, the author also cross-referenced the accounts he found with evidence from other major archives, diaries and sworn testimonies of key protagonists.

What might be most helpful to historians, who are still unsure of how credible the allegations are of a plot by Hitler to kidnap the pope, is the gendarmes’ detailed plan of action to protect the state from incursion and the pope from capture.

While there is still no proof that the possible invasion was either an empty threat or an actual planned operation, Catananti wrote that the fear and risk were real, according to documents he found in the gendarme archives.

The draft plans drawn up in mid-August 1943 by the gendarmes with input from the Swiss Guard as well as the final formal plan approved by the Vatican secretary of state Sept. 1, 1943 — one week before the Germans took control of Rome — are of great historical value, he wrote. They represent, for now, “the singular and exclusive official documentation on the hypothetical invasion of the Vatican and the kidnapping of the pope.”

A key directive from the secretary of state was that the gendarmes and the Swiss Guard engage in a form of “energetic” yet “passive defense.”

All entrances and points of potential access were to be fortified with additional metal supports and even sandbags. Additional guard posts and patrols were set up and the Vatican fire brigade was authorized to use its equipment as water cannons to keep invaders at bay.

If the Vatican City State border were breached, all Vatican residents were to head to the Apostolic Palace, which would then be sealed off with guards standing at the ready. Weapons could be used only for legitimate self-defense or fired only if ordered by the guards’ superiors.

Enough food and rations for everyone were to be stored in rooms in the palace under the Sistine Chapel, and staff from the maintenance department and health clinic were to have potable water and proper sanitation available.

Vatican medics and pharmacists were also to be prepared to provide medical assistance for any casualties in case of “an active defense” of the palace. In case of an air raid, everyone had to be led out of the Apostolic Palace and to the appropriate shelters near the medieval-era St. John’s Tower.

Any time guards were off duty, they had to remain in uniform and in their barracks so they could be immediately called into action, ready with their rifles and pouches of ammunition.

Though surrounded by walls, Vatican City State was not built like a fortress, and the gendarmes’ draft plans list numerous vulnerabilities, including all the gates, archways and walled sections that were easy to climb.

Small groups of armed Roman citizens made themselves available to guard the external border, particularly by the train trestle leading from Rome into Vatican City.

With Vatican guards spread out over a number of extra-territorial properties, the number of guardsmen available for the pope and palace defense plan was modest: just 200 men total from the gendarmes, Swiss Guard and fire brigade and another 20 from the ceremonial Palatine Guard.

If at any point the palace were breached, guardsmen had to be ready to go to the papal apartments, join the pope’s personal Noble Guard “and create a shield with their own body” to protect the pope.

While there was no attempted kidnapping of the pope, Vatican City State was bombed Nov. 5, 1943, by an unidentified low-flying aircraft. Four of the five bombs caused considerable-to-minor damage to a number of buildings and infrastructure.

A number of Vatican properties throughout the city and the papal villa of Castel Gandolfo had been hit by Allies multiple times as they advanced against the Germans in 1944, resulting in hundreds of casualties. The papal villa had become a shelter for about 6,000 people — mostly women and children — who were local residents and refugees seeking protection from the pope.

Catananti wrote that the surviving documents — some were destroyed in the 1970s from water damage after a pipe burst — showed the many ways the Vatican tried to navigate two completely different tracks: enforcing respect for its sovereignty and neutrality in a time of war and opening its arms to anyone in need.

“Even if the written orders to the gendarmes were to ‘turn away’ people, the actual praxis being followed was ‘welcoming’ people. The words of the Gospel were, in essence, the true law to be respected,” he wrote.

— By Carol Glatz, Catholic News Service.