By Gina Christian, Catholic News Service

Some six decades before Elon Musk began fretting over blue checks on Twitter accounts, the Catholic Church issued in-depth guidance on all forms of social communication — including those yet to be invented.

“The church recognizes that these media, if properly utilized, can be of great service to mankind,” declared the Decree on the Instruments of Social Communication, called “Inter Mirifica” (“Among the Wonders”). It was promulgated in 1963 as one of the first documents of the Second Vatican Council.

The text also noted “men can employ these media contrary to the plan of the Creator and to their own loss.”

“Inter Mirifica” is one of numerous church documents that explicitly address how news, arts and entertainment — delivered through a variety of channels — can and should benefit both the individual and society.

From ancient times to the present, Catholic teaching has stressed in increasing detail the importance of truth, charity and morality in social communications, while denouncing slander, propaganda, gratuitous representations of evil and other abuses.

Scripture is filled with such exhortations: the Eighth Commandment (Ex 20:16; Deut 5:20) forbids words or deeds that are offenses against the truth, which finds its source in God himself.

The psalmist implores the Lord to “set a guard … before my mouth, keep watch over the door of my lips” (Ps 141:3), while the Letter of James concludes “no human being can tame the tongue (which) is a restless evil, full of deadly poison” and capable of blessing and curses (Jas 3:8-9; cf. Jas 3:1-12).

As media have evolved, the church has sought to balance optimism and gratitude with concerns for the individual and the common good. Popes, theologians and faithful have worked to ground communications in a moral framework, so that everything from books to blockbusters to blogs can be placed at the service of the Gospel.

That undertaking was already underway as early as the sixth century, when Pope Gregory I identified four kinds of communication based on content and style.

According to Gregory, evil presented without condemnation (“mala male”) can incite further evil, while disapproving depictions can elicit good (“mala bene”). Conversely, what is good can be upheld in charity (“bona bene”) or derision (“bona male”).

A millennium later, Pope Sixtus V established the Vatican Printing Press, and in 1861 the first edition of L’Osservatore Romano, the daily newspaper of Vatican City, was issued.

By then, the first Catholic newspaper in the U.S. was nearing its fourth decade. The U.S. Catholic Miscellany was founded in 1822 by Bishop John England, the first bishop of Charleston, South Carolina. And U.S. bishops had already begun tackling concerns over the moral impact of books and newspapers.

At the First Plenary Council of Baltimore, convened in 1852, the bishops urged parents to guard children against morally objectionable texts, calling for curriculum materials “in Catholic schools and colleges (to) be purged of everything contrary to faith.”

Catholics also were asked to go on the media offensive by countering such materials with “orthodox newspapers and books.”

In the 20th century, the motion picture industry prompted further reflection and action by the church. As calls for regulation sounded, Jesuit Father Daniel A. Lord collaborated with movie studio heads to craft a 1930 production standards code.

Shortly thereafter, the U.S. bishops founded the National Legion of Decency (later the National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures), successfully leveraging Catholics’ faith and purchasing power to ensure morally acceptable films.

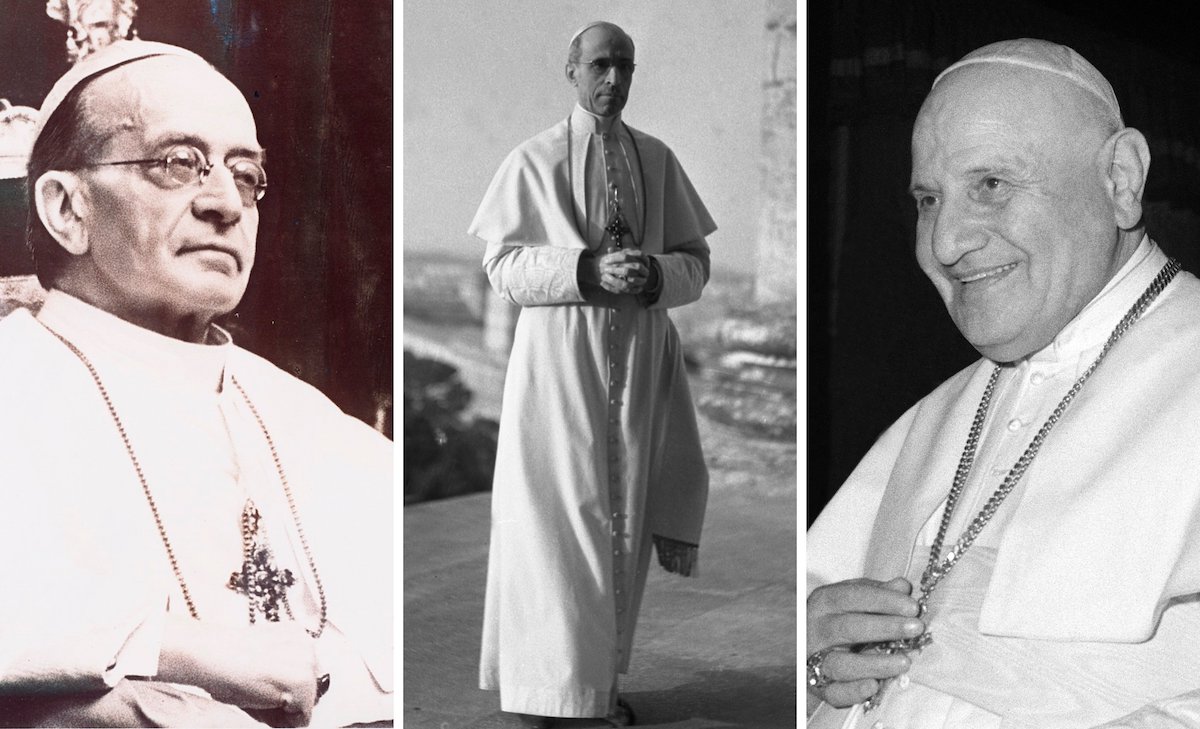

Pope Pius XI commended the Legion’s work in his 1936 encyclical “Vigilanti Cura” (“On Motion Pictures”), building upon previous observations in his 1929 “Divini Illius Magistri” (“On the Divine Teacher”), where he warned that “powerful means of publicity” such as cinema, radio and books — though of “great utility … when directed by sound principles” — can bode “moral and religious shipwreck” for the uncatechized, particularly youth.

His successor, Pope Pius XII, was even more specific in his 1957 encyclical “Miranda Prorsus” (“Absolutely Remarkable”).

Having established in 1948 what would become the Pontifical Commission for Social Communications (and, in 2015 under Pope Francis, the Dicastery for Communication), the pope urged the church to employ radio, television and film for “the sanctification of souls,” outlining the moral responsibilities of clergy, faithful and industry professionals regarding media.

Six months after the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, St. John XXIII, who made the Pontifical Commission for Social Communications a permanent office, penned his encyclical “Pacem in Terris” (“Peace on Earth”), asserting the right to free speech and publication “within the limits of the moral order and the common good.”

He also endorsed the right to freely investigate the truth and to receive accurate information about public events, along with the “utter rejection” of propaganda.

In the wake of Vatican II, St. Paul VI in 1967 instituted an annual World Communications Day.

Also following the council, the brief text of “Inter Mirifica” was fleshed out by the 1971 pastoral instruction “Communio et Progressio” (“Unity and Advancement”). The document reaffirmed the church’s stance on social communications as “gifts of God” intended to “unite men in brotherhood” and further the divine plan for salvation.

The text articulated the church’s “coherent vision” of communications, one that accounted for both “faith and the practical working” of media. With Christ as “the Perfect Communicator,” the document said communication is “more than the expression of ideas and the indication of emotion (but) at its most profound level … the giving of self in love.”

“Communio et Progressio” also looked to rapid expansions in the scope and complexity of social communications, through which “the responsibilities of the people of God (would) enormously increase.”

The instruction encouraged broadcasts of the Mass and other religious programming — which had already been instituted through Vatican Radio, as well as the Eurovision and INTELSAT networks — to reach the ill, the elderly and the religiously unaffiliated, “(carrying) the message of the Gospel to countries where the church is not.”

Several Catholic media pioneers were doing just that – among them, Blessed James Alberione, founder of the Pauline Family of congregations; Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, a scholar and popular radio and television personality; Mother Mary Angelica, who launched EWTN (Eternal Word Television Network); and Cardinal John P. Foley — dubbed “the patriarch of the American Catholic press” by the Catholic Media Association.

Cardinal Foley headed up the Pontifical Council for Social Communications and expanded the church’s use of media across multiple platforms.

Yet even as Catholic communicators became more proficient in media, St. Paul VI sounded a note of caution in his 1975 apostolic exhortation “Evangelii Nuntiandi” (“On Proclaiming the Gospel”).

While admitting “the church would feel guilty before the Lord if she did not use” social communications channels,” he emphasized these efforts must have “the capacity of piercing the conscience of each individual … as though he were the only person being addressed.”

Alongside mass media proclamations of the Gospel, he said, “the other form of transmission, the person-to-person one, remains valid and important.”

St. John Paul II, writing in his 1990 encyclical “Redemptoris Missio” (“The Mission of the Redeemer”), described “the world of communications” as “the first Areopoagus of the modern age,” capable of creating “a global village.”

He stressed that simply using media to spread the Gospel was insufficient; rather, it was “necessary to integrate that message into the ‘new culture’ created by modern communications” — a culture that was too often and tragically at odds with the Gospel, as Pope Paul VI had lamented.

Two years later, the Pontifical Council for Social Communications laid out the church’s pastoral priorities and responsibilities regarding media — as well as the need for a pastoral plan – in its instruction “Aetatis Novae” (“At the Dawn of a New Era”).

St. John Paul’s final apostolic letter, “Il Rapido Sviluppo” (“The Rapid Development”), rallied faithful to embrace media with courage and confidence: “Do not be afraid of new technologies … which God has placed at our disposal to discover, to use and to make known the truth.”

His two successors have echoed that message. Pope Benedict XVI launched the @Pontifex Twitter account, which now counts close to 19 million English-language followers alone, with eight other accounts in several other languages, including Spanish and Arabic.

Pope Francis has expanded still further the church’s engagement with media, even becoming known for his willingness to pose for “papal selfies” with faithful.

Yet at the same time — on what the Pontifical Council for Social Communications called a “chattering planet” — the pope has repeatedly called for another essential element in media: listening at all levels, in order to trace “the path of dialogue” as “a contribution to peace” (“Evangelii Gaudium,” IV, 238).